Steel tailored to industry’s needs

A team from the Warsaw University of Technology Faculty of Material Science and Engineering headed by Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng., is working on a new generation of nanocrystalline steel. Once developed, such steel stands a good chance of being implemented for production, primarily in tool manufacturing, but also in manufacturing of vital parts of machines and wear-and-tear products.

A team from the Warsaw University of Technology Faculty of Material Science and Engineering headed by Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng., is working on a new generation of nanocrystalline steel. Once developed, such steel stands a good chance of being implemented for production, primarily in tool manufacturing, but also in manufacturing of vital parts of machines and wear-and-tear products.

Conventional steels which are currently used for tool manufacturing (known as tool steels) are indeed hard and durable but yet brittle. Thus, the industry is on a lookout for alternative materials. These could be nanobainitic steels (i.e. steels with a structure composed of very fine grains, less than 100 nanometers in size). This is because they offer the right combination of high durability and plasticity and are likely to be well-suited to be made into various steel elements. On the downside, those steels are not hard enough for heavy duty tool applications. Hence the idea to combine the most desirable properties of tool steels and nanocrystalline steels known today.

Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng., received funding for the project titled “Development of a new generation of steel with a nanocrystalline structure with carbides” under the LEADER IX Program by the National Centre for Research and Development.

How does it work in practice?

“We use commercially available conventional steels which have the right chemical composition,” explains Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng. “We are looking for steels with a composition that comes close to that of nanobainitic steels and has a surplus of carbon and carbide-forming elements, e.g. vanadium, chromium or molybdenum.”

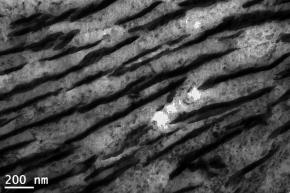

The nanobainitic steels known today contain bainitic ferrite (for the right durability) and retained austenite (for improved plasticity). The increased content of carbide-forming elements in the chemical composition of such steels will promote the release of carbides, or particles which improve the material hardness and durability.

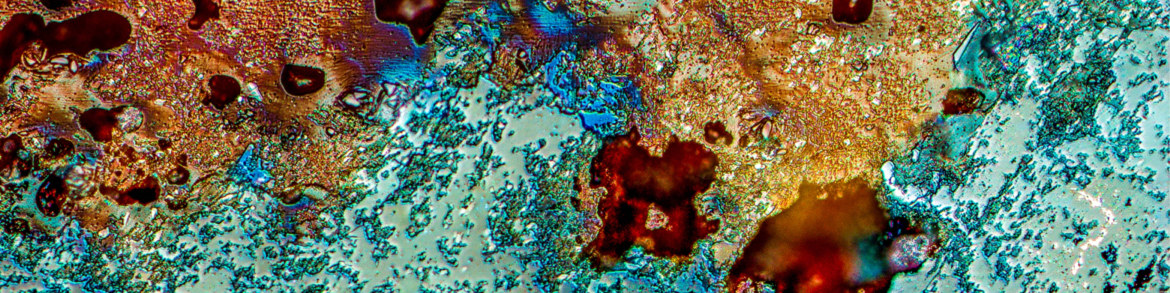

Microstructure of carbide-free nanobainite

“Our task is to design a precise heat treating process for selected commercial steels,” says Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng. “We have to select the temperature and time such that the microstructure of carbide-free nanobainite can be obtained to provide a matrix for carbides. You can think of it as a raisin cake. Fine-dispersive carbides will improve hardness and resistance to wear and tear from friction whereas the nanocrystalline matrix will provide high durability while retaining proper plasticity.”

This means that we will arrive at a combination of the best properties of conventional tool steels and known nanobainitic steels. The steel with a microstructure designed by the WUT team will be ideal for the production of molds for plastic, dies or punches.

“By varying the heat treatment parameters, we can steer the steel phase composition and properties to a wide extent,” says Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng.

Form the computer to the furnace

A number of tests must be carried out for such new generation of steel to be put to use. Although heat treatment is the focus, furnaces are by no means the key. The scientists use computer simulation of phase transitions to model the heat treating process. They use a dilatometer (i.e. an instrument that measures volume changes in the prepared samples in response to heating) and perform microscopic testing (under light and electron microscopes).

“Once we achieve the target microstructure, tests are repeated in laboratory furnaces,” says Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng. “Our tests have so far confirmed that the heat treating processes of our design can produce a favorable steel phase composition and microstructure.”

With implementation in mind

The scientists are working on shortening the duration of individual processes and take the approach of design for implementability. They have dealt with nanostructuring of steel for almost a decade now and they know their capabilities as well as the needs, expectations and limitations of business.

“There are other methods of development of nanocrystalline structures such as equal channel angular pressing, hydrostatic pressing, consolidation of nanopowders or crystallization of metallic glasses,” explains Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng. “The likely problem of those is that you first produce the material and only then you can make it into a specific item. In addition, the methods I mentioned enable production of relatively small-sized construction elements at this time, making their applications very limited. Our method ensures that nanostructure is developed throughout the volume of the material in an already finished element or steel product.”

Special chemical compositions of steel to facilitate the creation of nanobainitic structures are being designed elsewhere in the world. “Even if an ideal structure is obtained that way, there will be a problem of persuading steelworks to produce a new steel type, or businesses to apply a new and previously unknown steel grade in their manufacturing processes,” says Krzysztof Wasiak, M.Sc., Eng. “On top of that, the heat treating processes which lead to the development of nanostructures and are proposed for such steels tend to be time-consuming, and thus uneconomic for manufacturers.”

The scientist hastes to assure that the innovative heat treating processes designed at WUT Faculty of Material Science and Engineering are of relatively short duration and are suitable for implementation in industrially available furnaces thus sparing the need to change any existing plant or machinery.

The project includes the development and testing of the technology in the production environment or under near-real-world conditions but the implementation process itself is not part of the LEADER program. The project is scheduled for three years.